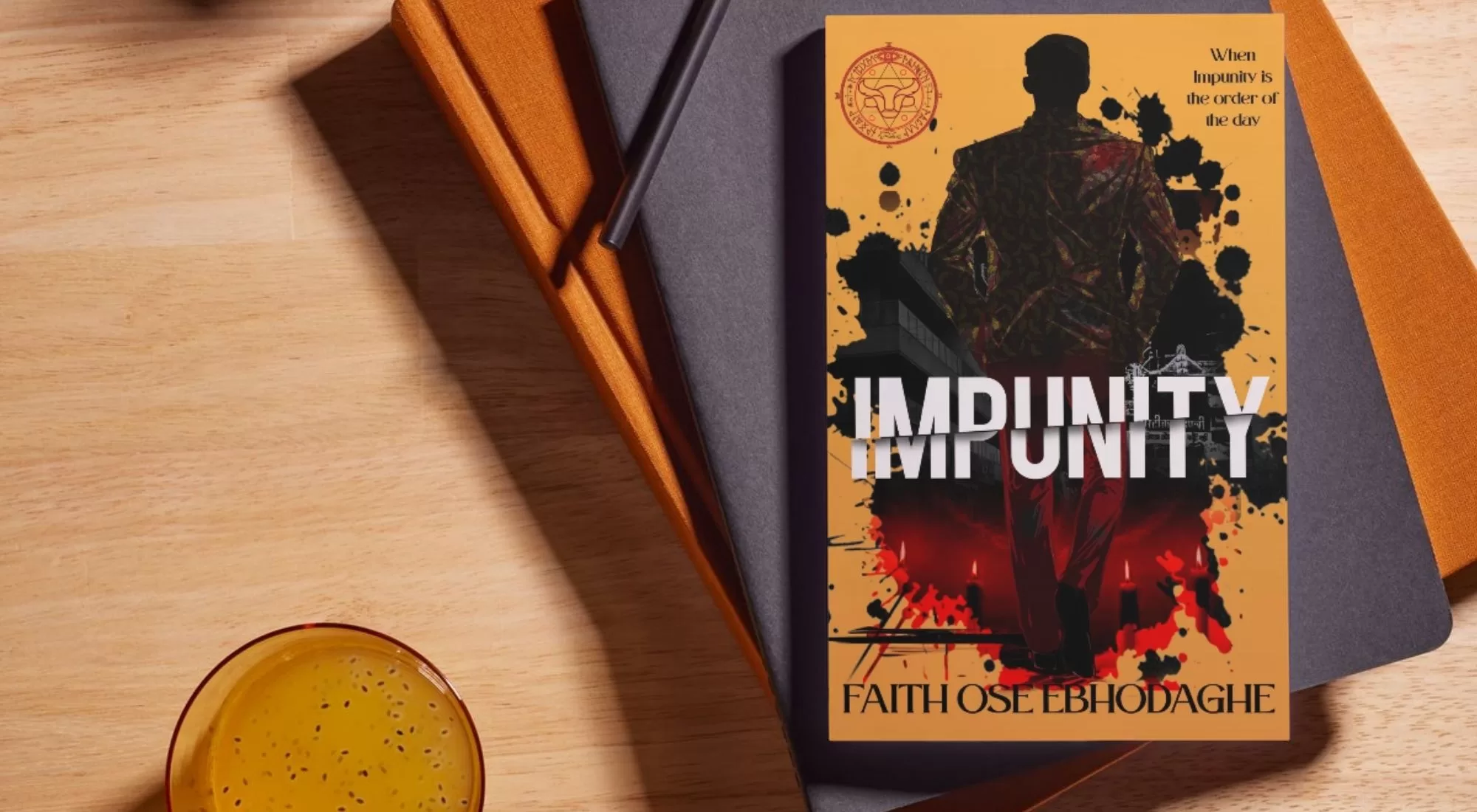

FICTION | JALI BOOKS | 2025 | 275 PAGES

“Corruption does not begin in the heart of elders—it is nurtured in classrooms, whispered in school hallways, and justified in the homes of ordinary people. It is a seed sown early, watered by impunity, and harvested by those who rise to power with no regard for justice.” — Faith Ose Ebhodaghe.

The above captures the story packaged in Impunity, a story embodied in two key characters that fittingly make the novel three parts. In the lives of the characters, we see that impunity can mean many things. In the first part (chapters 1-5), we meet Aza, a young boy enrolled in a boarding house. There, he encountered bullying. It rattled his spirit. The hostel prefect, Jude, became a thorn in his flesh until, giving in to crime as a result of lack of contentment, he succumbed to a lifestyle from which he couldn’t repent. Upon becoming a member of Yhesus fraternity, he quickly assumed the leadership and embodied terror and impunity. He watched his school and teachers enable corruption; it sowed a seed. Aza’s character tells how young minds are introduced to deceit and cultism. Also, it reveals that innate pursuit of power at any cost lurks in man. In Aza Briggs’ boarding house experience, we recall the world of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, that truth striking us that young people are utterly innocent; they have the potency for despicable things. We see something of the sort in Malla Nunn’s When the Ground is Hard; cliquism is borne of the desire to oppress and easily leads to it. The novel sheds light on the “dark intersection of politics and the occult, where wealth is gained through sinister means, and power is maintained through betrayal and bloodshed” (iii).

In what can be classified as the second part (chapters 6-10) we meet Adonis (and his friends) – symbol of the poor and those who suffer the clampdown of impunity in the land. Adonis, like many a young person, sought to enjoy the time of youth but was met with illegal strictures from those meant to facilitate the enjoyment of their civic life. But ours is a broken society, the impunity of law enforcement officers. Look how laughable the idea of having a search warrant before searching a suspect. In Adonis’s experience, we see what young people these days face. But in his very story we see juvenility and the honest struggle of the young (cf. 119). Adonis and his friends would spend time in the cell. Their experience is another form of Ose’s exposition of the impunity within the land, even cellmates lord and bully; the refrain remains “some animals are more equal than others” (cf. 131).

The tragedy of such impunity is summed up in this expression:

“So he’ll just go like that? No one held accountable?” Adonis shook his head. “That’s crazy” (171).

And what is more? For the little hope being mustered, the snuffling realisation comes in this form:

“No, Reana.” He looked at her seriously. “You can’t fight this system. It’s too corrupt. If you try, they’ll either throw you in jail or kill you. Please.”

How about the impunity that comes in the form of rape? In Nioma’s sad experience that led to fatality, we see the brazenness in many a man, that irritating delusion that one can get a feel of a woman’s body whenever an urge beckons. How about the impunity that comes with the desire of many a young man wanting to make money through fraud, and those who toe the path of organ trafficking and other dehumanising means? The novel casts the searchlight on them as well, only they’re not well developed therein.

If the novel has a crux, then it is the exposition of police brutality, seemingly an immortalising of the EndSARS protest that led to the 20/10/20 dark moment in Nigeria’s history, especially in regards the youth. So much irony for a country whose national life is anchored on the mantra: “to pass to our children a banner without stain.” Indeed, this story confirms the position of the author that ours is a society that enables impunity, the silence of many makes for complicity, and as seen in the very last act by the Media, in the end, history is rewritten to turn villains into heroes. The author leads us to ask “But at what cost? When the sins of one generation become the curse of the next, who truly pays the price?” (iii).

The thing with impunity is that everyone suffers from its existence, following the principles associated with Martin Luther King Jr, viz “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” and “no one is free until everyone is free.” Unfortunately for the plot, Aza did not know that the fruit of his impunity would recoil on his head as seen in what resulted in an incestuous relationship between his kids. Suffice to say, if police don’t brutalise you, a cultist may manhandle you; if a failed law system doesn’t deny you justice, a quack doctor will end your life; if a lecturer doesn’t frustrate your learning, a civil servant will enervate you. Impunity touches everyone in one way or another.

May it not be the lot of this Nation, especially of her youth, what it was for Reana: “Now, that day would never come. He was already gone, and the questions she had carried for years would remain unanswered” (254). And while the clock still ticks, let the Nation hear the wisdom of her foremost oracle: “This boy calls you father, do not bear a hand in his death.”

At the end, we ask, what breeds impunity? It is the principal that bends the rule, the teacher watching bullies do their thing without intervening; it is Felix betraying friendship and serving as a mole; it is the police collecting bribes on the roads; it is dysfunctional families, and laws that refuse to work.

The novel is essentially fiction, and as the author prefaced it, doesn’t make any pretension to answering questions or proffering solutions. Nevertheless, we can turn to Dul Johnson’s ‘Why I Tell Lies for a Living’ to make sense of the dilemma. The fact of the matter is that fiction is the lie by which writers tell the truth; and if Aminata Forna is right in saying “to know a nation, read its writers,” then in reading Faith Ose Ebhodaghe, we know something of Nigeria: a land marked by impunity. Here, the rich and powerful do whatever they like; even the poor have their way with recklessness. The law is not just blind; it is lame and handicapped. If the novel is anything, “It is a mirror held up to a nation fighting with its demons. It is a warning, a revelation, and, perhaps, a call to those who still believe that change is possible”, as the author herself puts it.

Izang Alexander Haruna is a poet, literary critic, and educator. His first book is Letters to 42 Writers (2024). Izang’s published works span multiple genres, including poetry, essays, book reviews, and literary criticism. His writings have appeared in renowned publications such as Boys Are Not Stones Anthology, Jalada Africa, Brigitte Poirson Poetry, AFAS Review, Unijos Echo, The Gadfly Philosophical Magazine, and The Nigerian Review.

You must be logged in to post a comment.